Double Declining Balance DepreciationDefined with Formula, Calculation & Examples

One cannot deny the contributions of long-term assets such as buildings, machinery, and equipment to a business’s revenue generation.

Without a building or space to house the manufacturing function, the business won’t be able to manufacture a single unit of product.

Not to mention the machinery and equipment that the personnel use to manufacture the products.

There’s a reason why businesses invest in these assets even if they can be fairly expensive.

That said, these assets don’t last forever.

They will gradually lose their value either through the passage of time or wear and tear through continued use.

For example, think of a laptop.

A laptop will perform optimally when it’s still brand new and it may continue to do so for a year or two.

But after that, you will notice some wear and tear either in the hardware or software.

You may notice that some keys on the keyboard don’t feel as they were when the laptop was brand new.

You may also notice some scratches here and there and finally, you may notice that the laptop itself is slowing down.

While it would be ideal if you can use the laptop forever, you’ll have to replace it eventually.

And that also goes with other long-term assets.

They will eventually be unable to perform at a level that is required of them.

So really, you can no longer get any economic benefit out of them. When it comes to that point, they virtually lose their value.

We record this gradual decrease in value via depreciation.

There are several methods to account for depreciation, the most common one being the straight-line method of depreciation.

However, we will be discussing another method of depreciation in this article.

We refer to this method as the double declining balance method of depreciation.

What is Depreciation?

But before we discuss the double declining balance depreciation, let’s have a crash course on depreciation first.

Depreciation refers to the act of allocating the cost of a long-term tangible/physical over its estimated useful life.

Long-term assets gradually lose their value through wear and tear.

Depreciation represents that gradual decline in an asset’s value.

It also allows businesses to spread out the cost of an asset over the time that it benefits them.

Long-term assets such as machinery and equipment aren’t cheap.

As such, recognizing their full cost as an expense at the time you acquire them will put a huge dent in your profits for that accounting period.

Besides, doing so contradicts the matching principle in which expenses should be recognized at the same time as the revenue they are related to.

Long-term assets can offer you economic benefits for more than a year.

For example, a piece of machinery used in the manufacturing of a product will serve you for several years.

We refer to this number of years as the asset’s useful life.

An asset’s useful life is usually estimated depending on how long the business expects to benefit from it.

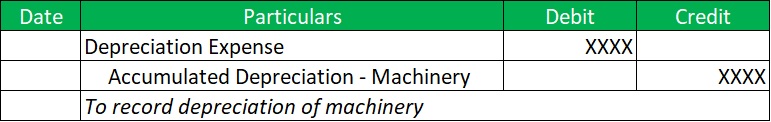

With depreciation, a business will recognize depreciation expense every accounting period (usually monthly).

The business also recognizes a corresponding accumulated depreciation account as the credit entry.

For example, if a business wants to recognize depreciation expense for a piece of machinery, it will enter the following journal entry:

The amount of depreciation expense to be recognized will mainly depend on three factors:

- The original cost of the asset

- The estimated useful life of the asset

- Depreciation method used

At the end of the asset’s useful life, it becomes fully depreciated.

What is the Double Declining Balance (DDB) Depreciation Method

The double declining balance depreciation method is one of the methods of accounting for depreciation.

It’s one of the many variants of accelerated depreciation that recognize higher depreciation expenses during the early years of the asset.

In the double declining balance depreciation method’s case, it recognizes depreciation expense at double the rate of the standard declining balance method.

Do note though that whatever depreciation method you use, the total depreciation expense that you can recognize for an asset will always be the same.

Whether you use the straight-line method or double declining method, the total depreciation expense related to an asset will still be the same.

What DDB does though is that it allocates more depreciation expense in the asset’s early years at the cost of lesser depreciation in its later years.

The rationale behind this is that some assets are more useful during their early years.

As such, they would be used more resulting in more wear and tear on the assets.

Because of this, it would only be appropriate to record higher depreciation expenses in their early years.

That and some assets just lost value quicker than the others. Just take a look at smartphones.

Since newer and better models are released almost every year, older models quickly lose their value.

As for tax implications, recording higher depreciation expenses would result in higher tax deductions.

This is in turn results in lower tax liabilities.

With DDB, a business can record higher depreciation expenses during an asset’s early years compared to using straight line depreciation.

The caveat is that the business will record lesser depreciation expenses during the asset’s later years.

By using DDB, a business can defer its income taxes to the later years.

This is especially advantageous for new businesses that are still building up their revenue generation.

Computing Depreciation Using the DDB Depreciation Method

Computing depreciation with DDB is more complicated than with the straight line method.

That said, it isn’t that much harder.

First, we need to identify the rate of depreciation that we will apply.

This can be computed by dividing 1 by the useful life of the asset.

With DDB, we multiply that rate by 200% or 2, hence “double”. Put into formula form:

The double-declining depreciation rate is calculated by dividing 1 by the asset’s estimated useful life and then multiplying the result by 200%.

For example, let’s say that an asset has an estimated useful life of 5 years. The double declining depreciation rate will then be:

Double Declining Depreciation Rate = 1 ÷ Estimated Useful Life x 200%

= 1 ÷ 5 x 200%

= 40%

This is the rate that we will use to compute the depreciation expense for the period.

To compute the depreciation expense, we apply the rate of depreciation to the net book value of the asset at the time of depreciation.

Put into formula form, it should look like:

Depreciation Expense = Net Book Value of the Asset x Double Declining Depreciation Rate

Where:

Net Book Value = Original Cost of the Asset – Accumulated Depreciation

For example, let’s say that the asset has a net book value of $2,000. The depreciation expense will then be:

Depreciation Expense = Net Book Value of the Asset x Double Declining Depreciation Rate

= $2,000 x 40%

= $800

Do note the following that you cannot always use DDB for the whole life of the asset.

Usually, during the asset’s last year, DDB is no longer applicable.

Depreciation expense will instead be the net book value of the asset less its salvage value.

Example using the Double Declining Balance Depreciation Method

The PAC company acquired a piece of machinery for $30,000.

The PAC company estimates that it has a useful life of 8 years and will have a salvage value of $2,500 by then.

PAC company’s management decides to use the double declining depreciation method to account for the asset’s depreciation.

Our task is to prepare a depreciation schedule for the asset.

First, we need to determine the double declining depreciation rate:

Double Declining Depreciation Rate = 1 ÷ Estimated Useful Life x 200%

= 1 ÷ 8 x 200%

= 25%

Now that we have our depreciation rate, we will apply it to the asset’s net book value to compute the depreciation expense.

For the first year, the asset’s net book value is $30,000:

Depreciation Expense = Net Book Value of the Asset x Double Declining Depreciation Rate

= $30,000 x 25%

= $7,500

For the second year, the asset’s net book value is $22,500 ($30,000 – $7,500):

Depreciation Expense = Net Book Value of the Asset x Double Declining Depreciation Rate

= $22,500 x 25%

= $5,625

As we continue to compute the asset’s depreciation expense for each year, we will arrive at the following schedule:

Notice that the depreciation expenses for the earlier years are higher than the later years.

This represents the accelerated decline of the asset’s value.

Notice also that in the last year of the asset, we didn’t use the DDB formula.

Instead, we compute for the depreciation expense by subtracting the asset’s salvage from its net book value:

Depreciation Expense = $4,004.52 – $2,500.00

= $1,504.52

This is to ensure that the asset’s net book value at the end of its useful life will always be equal to its salvage value.

FundsNet requires Contributors, Writers and Authors to use Primary Sources to source and cite their work. These Sources include White Papers, Government Information & Data, Original Reporting and Interviews from Industry Experts. Reputable Publishers are also sourced and cited where appropriate. Learn more about the standards we follow in producing Accurate, Unbiased and Researched Content in our editorial policy.

Cornell Law School "26 CFR § 1.167(b)-2 - Declining balance method." Page 1 . February 11, 2022

The University of Memphis "CHAPTER 12 – Depreciation Methods " Page 1 - 9. February 11, 2022

California State University Northridge "Depreciation, Amortization, Depletion" Page 1 . February 11, 2022